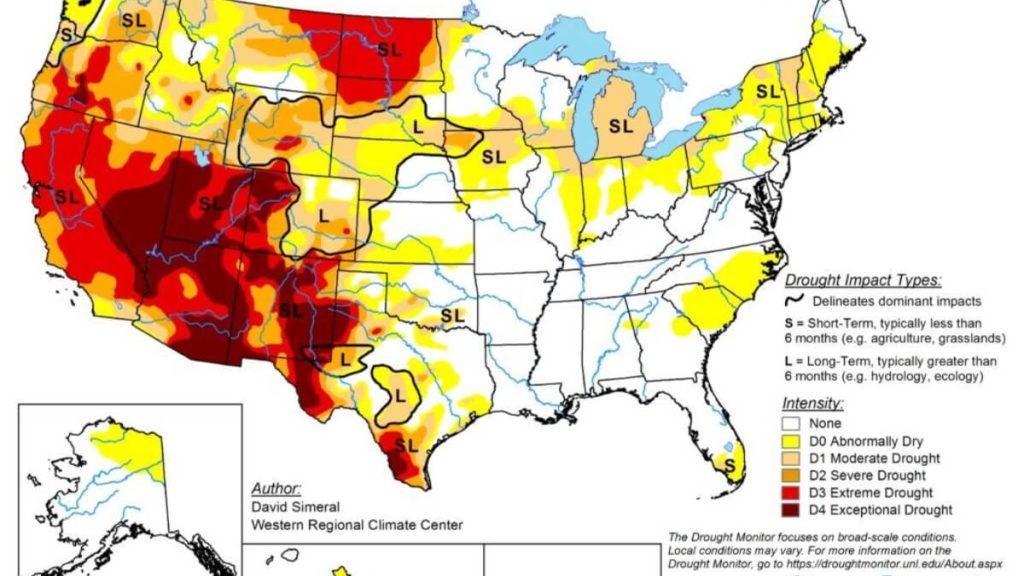

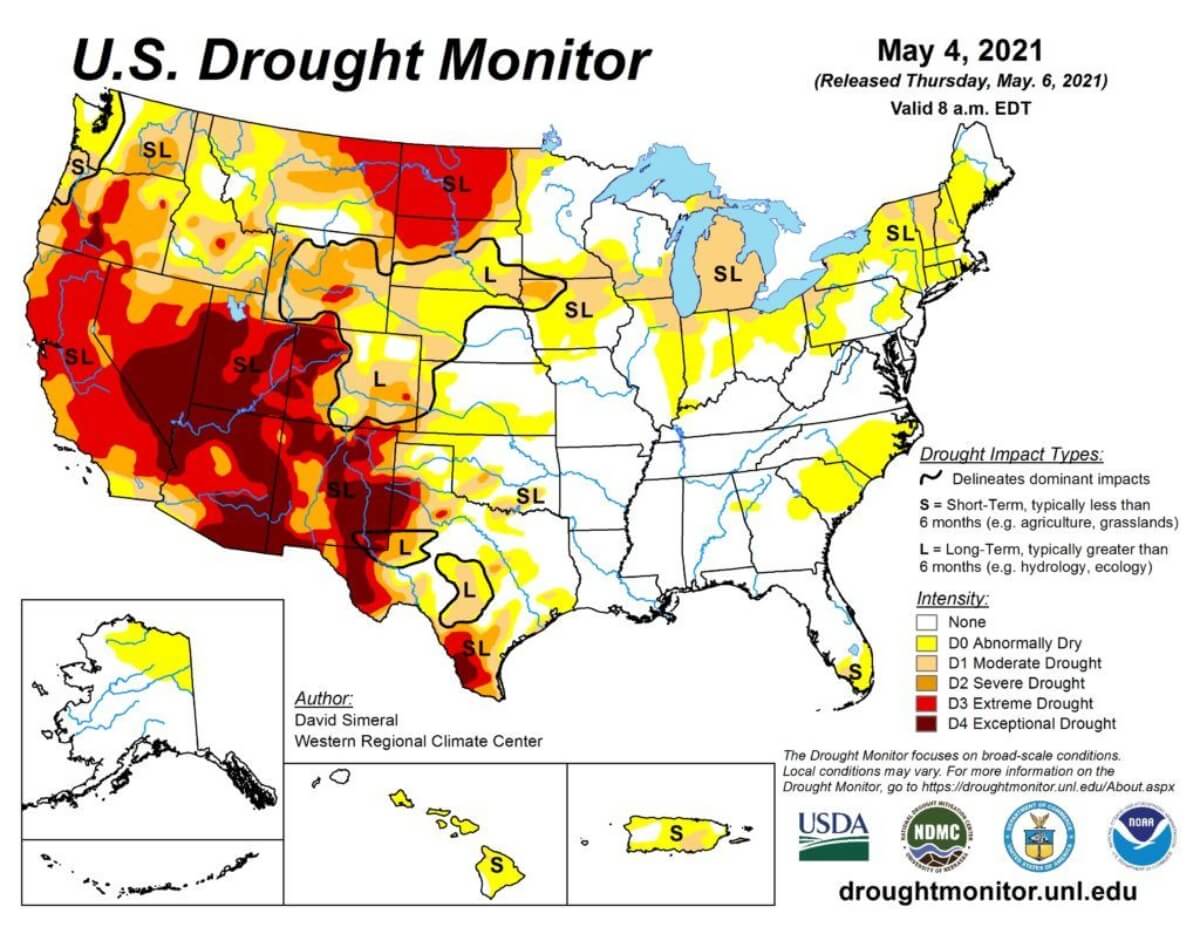

(Map courtesy of the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

(This is the latest installment in a series focused on cultivation planning for marijuana and hemp growers. The previous installment is available here.)

Water is a must for successfully producing hemp and marijuana, so making sure to have enough for the growing season and tapping into an irrigation system are critical tasks for cannabis cultivators.

The task is even more important this year, when many parts of the country are facing drought conditions.

Growers can ensure they have an adequate water supply by:

- Buying or leasing water shares.

- Managing water supply.

- Irrigating through pivot, drip or flood systems.

- Maintaining soil moisture through regenerative practices.

Securing water shares

While hemp and marijuana are generally forgiving crops that thrive in drier conditions once they get established, no crop can do without water – including cannabis.

“We can definitely say for a CBD crop and for hemp in general to be grown to its potential, it definitely prefers irrigation, whether that be drip, flood or pivot,” said Bodhi Urban, vice president of research and development for High Grade Hemp Seed in Longmont, Colorado.

Cultivators producing marijuana as well as hemp flower and biomass for cannabinoids must ensure they have the right balance of water to maximize their crop’s growth potential and yield – because under-watering and overwatering plants can trigger a stress response and affect crop quality.

Depending on the geography and the climate where they produce cannabis, growers will have different water needs and options for accessing water.

In the West, for example, local ditch and water associations offer the option for growers to buy or rent water shares. So growers should get in touch with those groups locally to find out about the availability of water and current water rates.

“Generally, you’re going to have to work off the ditches that run to your farm, so finding shares through that ditch company is going to be your only option,” said Ben Grinnell, farm manager for Center Pivot Group, a division of New Mexico-based Santa Fe Farms.

Rates can change drastically from one ditch association to another, depending on the availability of water that year.

“In a season with heavy rain and lots of snowpack, there’s going to be a surplus of water and the water rates that year will be a lot lower, whereas if we’re in drought conditions, water rates will be exponentially higher,” Grinnell said.

In wetter parts of the country, growers may be able to get away with using well water from their farms rather than renting water, and rely on natural precipitation once crops get established.

“We’ve seen guys go the whole season without having to water,” Grinnell said.

Out West, though, additional water “is essentially a must for a majority of crops,” Grinnell added.

Water supply

An irrigation pond is essential for maintaining a strong supply of water through the season

Western growers working with a ditch system will have water delivered to their pond through the association, which will monitor how much water a grower receives.

This year is shaping up to be a dry one, which means states dealing with drought conditions may start cutting off water.

Growers should try to replenish their irrigation ponds early and often to ensure they have enough water through the season and to safeguard against potential natural disasters such as wildfires, Grinnell said.

“Make sure that in the mid and late season you’re not exhausting all of your water” before plants get into flowering stage, Grinnell said.

“One thing about water is, once it’s downstream from you, you’re never going to have the opportunity to get it back.”

Irrigation systems

Every farm and field is different, so when it comes to irrigation, cultivators need to consider their own crops and needs rather than adhering to any kind of cookie-cutter application, Grinnell said.

“The most important thing when you’re growing your crop is is knowing your ground, knowing your crops and your genetics, and listening to the plants, seeing what they have to say, being hands on with the crop every day,” he noted.

But there are general guidelines for which irrigation systems work best for each crop.

For outdoor-grown marijuana and hemp cultivated for flower and biomass for cannabinoid production, growing in raised beds with drip irrigation may be the most efficient method, while also allowing growers to provide nutrients directly to the plants through fertigation, Grinnell said.

Drip irrigation delivers a low-pressure supply of water directly to the plant’s roots through tubes or tape running along a row of plants, above or below ground.

This method offers more precision and keeps leaves dry, with less risk of disease, and can be automated.

Drip irrigation is ideal for boutique or craft flower and biomass production, in the 20- to 50-acre range, Grinnell said. But as farms scale up in size, drip irrigation can become cost-prohibitive due to the labor costs involved with installation and removal at the end of the season.

Cultivators may want to consider pivot irrigation or even flood irrigation as an alternative.

When it comes to agronomic growing methods typically used for industrial hemp for grain or fiber production, pivot irrigation is ideal, Urban said.

Often used in traditional row crop farming, pivots are essentially large sprinklers or booms that pull water from a source and spray crops from an automated rotating pipe.

This method uses less water and can be automated, but the water can land on the leaves and not make it down to the soil.

“For a direct-seed industrial (crop) you do have the risk of losing some of your seed without starting with a pivot,” Urban said, adding that a crop’s germination rate is higher with adequate water.

Flood irrigation – in which farmers pump water from their irrigation pond to the field and cover the surface of the soil – may be the most cost-effective method, especially if cultivators have access to affordable or free water.

But it depends on when cultivators plant and what kind of inputs they use. Direct-seeded crops may wash out with this method, and flood irrigation can also cause over-watering, which can promote mold and disease.

Maintaining moisture

Farms using regenerative agriculture practices such as no-till farming are showing that soils maintain moisture better than more conventional practices, Grinnell said.

Growers concerned about water can look to using regenerative practices to maintain moisture.

“If you’re not going through the field and deep plowing, your ground is going to hold a lot of that moisture through the winter season and the spring season,” Grinnell said.

Whereas using conventional farming practices, he said, “every time you make a pass through that soil, every time you turn it, you’re getting tons of evaporation.”

Laura Drotleff can be reached at [email protected]