NORML Founder Keith Stroup

For NORML’s 50th anniversary, every Friday we will be posting a blog from NORML’s Founder Keith Stroup as he reflects back on a lifetime as America’s foremost marijuana smoker and legalization advocate. This is the third in a series of blogs on the history of NORML and the legalization movement.

Hunter S. Thompson – a Natural Ally

One of the true pleasures of being involved with NORML over these many decades has been the opportunity to meet a lot of fascinating and interesting folks – some famous, others infamous – that I would never have had the occasion to meet were I working at some more traditional job. People such as Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, High Times founder Tom Forcade, Willie Nelson, former US Attorney General Ramsey Clark, Harvard Medical School Professor Lester Grinspoon, early prohibition victim and poet John Sinclair (founder of the White Panther Party), actor Woody Harrelson, actor Tommy Chong, comedian Bill Maher, travel writer and tour guide Rick Steves and many others (many of whom I hope to write about in subsequent blog posts.

But without question, one of the most interesting of this cast of characters was the writer and cultural icon Hunter S. Thompson.

The first time I met Hunter he was smoking a joint under the bleachers at the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami, FL. Along with Margaret Standish, the head of the Playboy Foundation (our initial source of funding) and a couple of others, we had driven my Volkswagen camper from Washington, D.C. to Miami to “attend” the Democratic convention. Of course, none of us were official delegates, and our real purpose was to try to use the national media attention that always accompanies a national political convention to publicize NORML and our mission of legalizing marijuana.

The prior Democratic Party convention in Chicago in 1968 had attracted so many anti-Vietnam War protesters that riots resulted and large numbers of protestors were beaten and/or arrested by the heavy-handed Chicago police. So the Democratic Party leadership decided to take a more permissive approach to protestors four years later. They basically welcomed all who wanted to come to Miami to bring their peaceful protests, so long as they stayed about three blocks away from the convention itself in a carefully fended-in park that was quickly nicknamed the “People’s Park.”

There were scores of groups in “People’s Park” protesting and advocating all sorts of issues and doing their best to stand-out from the crowd, which was no easy task. But so long as they remained in the park, the police left everyone alone, including the “People’s Pot Tree,” a tree where then smuggler and soon-to-be founder of High Times Magazine, Tom Forcade, sold baggies of marijuana to anyone who wanted it. More on Tom Forcade and the People’s Pot Tree in a future NORML blog.

It was opening night of the 72 convention and I had managed to get visitor tickets that allowed me to get inside the convention hall and listen to the proceedings. I was sitting in the stands listening to the speeches when, quite suddenly — and without any question in my mind — I smelled marijuana, and quickly realized it was coming up from down below. I looked below the bleachers and what I saw was a fairly big guy smoking a fairly fat joint. He was trying to be discreet, but it wasn’t working very well. I could see him hunkering in the shadows — tall and lanky, flailing his arms and oddly familiar. Jesus Christ, I suddenly realized, that’s Hunter S. Thompson!

Screw the speeches. I quickly found my way under the bleachers and approached as politely as possible.

“Hu-uh – What the fuck?!! Who’re you?!”

“Hey, Hunter. Keith Stroup from the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. We’re a new smoker’s lobby.” Easy enough.

“Oh. Oh, yeah! Yeah! Here,” Hunter held out his herb, “You want some?”

We finished that joint and began a friendship that lasted for thirty-three years.

Like every other young stoner in America I had read “Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas” as it was serialized eight months earlier in Rolling Stone. Hunter would soon gather great fame for himself, the kind of fame from which one can never look back. The following summer in 1973 “the Vegas book” – as he invariably called his signature work – would be released to extraordinary acclaim and Thompson would blaze into 20th Century Letters; but on the night I met him his star was still ascending. With his mass audience still in the very near future and his notoriety still at the fringe, he was in Miami working on his next book, Fear & Loathing On The Campaign Trail ‘72 and he was enjoying access to campaign managers, strategists, planners and candidates, the likes of which he would never see again.

His relative anonymity at that moment in the world of national politics allowed him to move freely and professionally inside the convention hall. Once Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72 came out with its gonzo allusions to splitting a tab of acid with NBC Nightly News host John Chancellor and its blunt evocations of presidential candidate Maine governor Edmund Muskie on methadone, Hunter would never again opt for insider status. George McGovern’s Campaign Director Frank Mankiewicz would later recall the book to be “the most accurate and least factual” account of the campaign.

You see, Hunter, who referred to himself as Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, based on a mail order diploma he had obtained as a joke, was a self-described political junkie and so am I, and that was the basis of our long friendship — that and a mutual predilection for fine drugs. Hunter was most stimulating and the most fun when he was debating politics. By the time I met him in Miami, Hunter had managed a campaign for the mayor of Aspen and had run for sheriff the following year. He lost by a handful of votes.

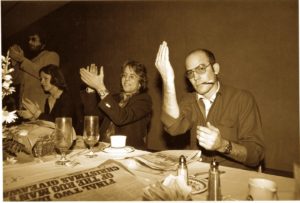

Founder Keith Stroup & Hunter S. Thompson at an early NORML conference

Hunter attended several of the early NORML conferences in the 1970s in Washington, DC, where he was a celebrity speaker whose name on the program assured a surge in attendance, and where he regularly invited most of the attendees up to his private room to get high, a thrill that made it all worthwhile. I was sometimes left with having to pay the hotel damages for what Hunter had done to the room when he got a bit carried away and slammed room service carts into the wall, but that was just the price of including Thompson, and it was a price I was quite willing to pay.

On one of my first visits to Aspen, in the mid-1970s, Hunter and his wife at the time, Sandy, invited me to join them at singer Jimmy Buffett’s wedding. It was at the home of Glen Fry, lead singer of the Eagles and a neighbor of Buffett’s. I was staying at the Jerome Hotel right in the heart of town, long before it was remodeled and made into the fancy hotel it is today. At that time it looked like a bordello, with fuzzy red covered sofas and old wooden stand-alone armoires that seemed right out of the 1890s. I loved staying at the Jerome; it felt like where one might have stayed during the silver rush a century earlier.

Hunter and Sandy came to pick me up at the Jerome, and the three of us took acid so we could fully appreciate the wedding. I can recall arriving at a beautiful home, with Buffett and his soon-to-be wife Jane looking like two Aspen celebrities, and the Eagles performing after the wedding from a balcony. It was truly a wonderful, unique experience, but I have to take that on faith, as I was tripping my ass off and don’t have much memory of the details.

For years, I would periodically find an excuse to visit Aspen, and spend a couple of nights hanging out with Hunter, recharging my batteries late at night, stoned to the back of my eyeballs, a little too drunk for driving but not for talking politics.

Hunter lived at this lovely small farm named Owl Farm, off a small country road about a mile or so from Woody Creek, home of the famous Woody Creek Tavern, about 7 miles outside of Aspen. Hunter frequently hung out at the Woody Creek Tavern, and because he was a local boy, they would save a table for him on the nights he generally came in for dinner, and perhaps more important, should they see anyone strange heading up the road towards Owl Farm — and they could see every vehicle that went by — they would call Hunter to warn him, in case he might need the advance warning.

Hunter S. Thompson at Owl Farm

An evening at Hunter’s place was a special experience. Because of staying up most of the night, he was usually sleeping late during the day, and then it took him a few hours to get up and get dressed, have breakfast and read the papers, and get set for the day, which by then was usually night. So I would not arrive until 10 or 11:00pm, when he was ready to see friends or work on his various writing projects, or sometimes both.

Hunter would be sitting in the kitchen, at the breakfast bar, which he used as his desk and base of operations, with a typewriter and fax machine within easy reach (he refused to use personal computers), and the remote control to his television set (the largest home screens available at the time) dangling from the ceiling on a cord, so he could always find it even in the most confusing times.

And there were literally scores, perhaps hundreds, of notes and faxes and letters and pictures, most with some scribbles from Hunter, either editing his original typing, or commenting on what someone else had said, and these items, along with many other objects de art, all stuck on the walls and the refrigerator and the kitchen cabinets and the lamp shades with scotch tape, or a tack or a paper clip. It looked as if he had saved every note he had ever written to anyone, or received from anyone, and wanted each and every one of them to be handy, in case he wanted to refer back to them quickly. It was his version of a filing system. On more than one occasion I would visit Hunter and see one of my own faxes stuck on the wall or a lampshade, so I knew he did sometimes move these around, or at least he added new layers.

Those private evenings with Hunter were truly some of the most enjoyable and stimulating times I have had the pleasure of experiencing in my life. We would sit and intellectually spar for hours on end, all the while smoking great weed (I would always bring some good marijuana to share with Hunter), drinking whiskey, and snorting Hunter’s cocaine. This would go on until either I decided I was about to drop, and I would announce my need to depart to get back to my hotel, or Hunter would decide it was time to start writing, and I would take the clue and say goodnight and make my way back to town.

In February of 2005 word came that Hunter had killed himself. He was sitting at his usual place, his command chair in the kitchen, and had put a handgun to his head and pulled the trigger. Hunter was dead by his own hand at the age of 67. His health had been failing him in the last couple of years, and he had had a hip replacement and was finding it difficult to walk, largely confined to a wheelchair. Whatever the reason for his taking his life at this particular time, it was not a total surprise to anyone who had known Hunter over the years.

He was generally a fun loving guy who would go to great lengths to play a practical joke on friends or to get a laugh. But he also had his dark times when he found the world a challenging place to survive, as most of us do at times, and he would sometimes talk of suicide. “Doomed” was one of his favorite words.

His last written words were: “No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun — for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won’t hurt.”

Along with 150 of his friends and family, including his celebrity friends Bill Murray, Jack Nicholson, Johnny Depp, John Cusick, and Sean Penn, and his artist/partner in crime, Ralph Steadman, on March 5th I attended Hunter’s memorial service at the Jerome Hotel in Aspen, an emotional but sometimes light-hearted six hour tribute with lots of alcohol and weed.

In 2007 the NORML Board of Directors awarded (posthumously) a Special Appreciation Award to Hunter, reflecting his life-long commitment to legalizing marijuana.